By Anton Tagliaferro

READ

Passive investment strategies continue to gain in popularity as large quantities of funds across the world are being invested in them at a time when most active managers are underperforming their benchmarks. It is also not uncommon to hear some commentators making statements such as ‘value investing is dead’ and ‘markets have become so efficient that there is no longer a role for active managers’.

On the other hand, other commentators like US fund manager Michael Burry – who shot to fame as one of the few US investors who bet against US mortgage-backed securities before the 2008 financial crisis – was recently quoted as calling the huge growth in passive investing through ETFs and index funds ‘a bubble’ while also claiming that ‘the trend to very large size among asset managers has orphaned smaller value-type securities globally’.

So how are passive and active investing defined?

Passive or index investing is based on the strategy of precisely tracking an index’s movements by buying a portfolio of securities that exactly replicates the composition of an index. This type of investing takes no view whatsoever on the underlying quality or value of the securities bought and held for the portfolio. By investing money on this basis, an investor’s returns in a passive fund will exactly replicate the underlying index’s performance over every time period. In addition, fees on index funds are generally much lower when compared to active funds.

Active investing, on the other hand, is based on the premise that active managers will construct their portfolios differently from the index to take advantage of mispricing opportunities in the market that the active manager has identified. By doing so successfully, the active manager aims to earn a better return than the underlying index over the longer term. Active managers’ fees vary but are generally higher than those of index managers, with many active managers also charging performance fees.

In the last few years as markets have risen ever higher, most index equity funds have outperformed most active fund strategies, and this has helped lead to their increased popularity amongst a growing number of investors.

So why have index funds outperformed active funds in recent times?

With the benefit of hindsight, given the fairly strong momentum-driven sharemarkets of the past few years, it should actually not be a total surprise that passive investment strategies have outperformed most active managers – especially value managers.

This phenomenon of passive managers doing better than most active managers is actually nothing new when in the mature stages of a bull market cycle – this is because it is often the most expensive, and at times the most illogically valued stocks that tend to lead the market up in the latter stages of any bull market. These are stocks which most research-based fundamental active managers – like IML – often cannot justify holding in their portfolios.

Although it is always difficult to judge exactly where we are in any equity market cycle, there is no doubt that the current cycle continues to be prolonged by central banks lowering interest rates to unprecedented levels, such as 0.75% in Australia and -0.5 % in Europe – and by continued quantitative easing in many parts of the world – such as Europe and Japan. This has kept massive surplus liquidity in the system looking for a home at a time of slowing economic growth and pressure on corporate profitability which is leading, in our view, to some irrational pricing in many sectors of the stockmarket.

‘The truth is that tracking an index closely in a bull market may satisfy many investors’ needs as markets rise but, clearly, when indices fall heavily it can cause havoc with many portfolios as they have over periods such as 2001, 2007-8 and 2011-2012′

IML Investment Director Anton Tagliaferro from 20 lessons from 20 years of investing

If one looks at previous market cycles one can again see this phenomenon where passive managers have outperformed active value managers, such as IML, especially in the latter stages of an equity cycle.

Consider the lead-up to the 2000 market peak. In 1998, the Fed aggressively cut interest rates three times following the massive problem at Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) hedge fund and Asian crisis in late 1997 – leading to a strongly performing technology sector as the US Nasdaq index exploded into life. In Australia, the market was led by News Corp, whose share price took off after the US’s largest internet service provider America Online (AOL) bid a huge price, using overinflated scrip, for media company Time Warner – a takeover that many said was the prelude for new tie-ups between internet service providers and ‘old economy ‘ media companies.

During this time, News Corp soon became Australia’s largest company, representing 18% of the Australian All Ordinaries Index and trading on a PE of well over 100 times earnings. The Nasdaq boom led many other high-flying stocks to valuations of tens of billions of dollars at the time on the Australian stockmarket. Now-defunct companies, such as One.Tel, Ecorp, Voicenet, Sausage Software and Solution 6, were stampeded as investors sought ‘new economy’ exposures on the Australian sharemarket. Incidentally, the merged entity AOL-Time Warner fell apart only a few years after the two companies got together.

Roll the clock forward to 2007 when, once again, following a prolonged period of easy monetary conditions (with rates in the US reaching a low of 1% in 2004), sharemarkets around the world were once again enjoying the benefits of a prolonged bull market. As disciplined value managers, IML’s Funds again seemed to be well off the pace and out of touch in 2005 and 2006, with our returns lagging the index and our Funds looking lacklustre vs many benchmark-driven peers and vs all index funds. 2007 was a time of great excitement in many sectors – with the US housing market in a huge bubble, thanks to the explosion in NINJA loans (no income, no job or assets) being made which caused a financial and US housing bubble that will go down in history as one of the biggest Ponzi schemes of all time.

As with 2001, the exuberance was once again not confined to the US, as the loose lending practices spread all around the world, including Australia.

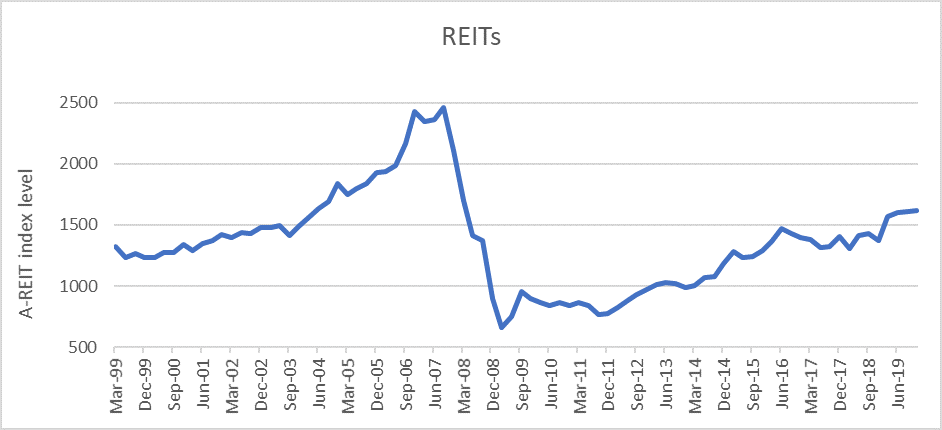

In the lead-up to the 2007-2008 sharemarket correction, few would remember that one of the best performing sectors on the Australian sharemarket at the time was the REIT sector as companies like Centro and many others used cheap debt to make hundreds of ‘dpu accretive’ but very low-quality acquisitions.

Many of these acquisitions seemed nonsensical at the time to logical investors like IML – we still recall well, for example, office trust GPT raising money and borrowing heavily to pay a huge premium to enter into a German housing development joint venture with Babcock and Brown which was meant to be very accretive (later abandoned). We also recall well smaller trusts, such as Melbourne-based APN Property Fund getting in on the action by raising fresh equity capital to acquire shopping centres in Romania on a 7.5% yield in their Australian-based listed fund on the basis that they were deemed to be ‘dpu positive’. (Romania was not part of the EU at the time, and anyone who knew much about Romania knew it was a pretty risky country in which to do business.)

‘Thanks to the excitement of many of these deals, the REIT sector grew to a not insignificant 10% of the All Ordinaries Index’

Thanks to the excitement of many of these deals, the REIT sector – which IML steered well away from – grew to a not insignificant 10% of the All Ordinaries Index. Other ‘hot’ companies that seemed to do no wrong were the likes of Allco Finance, MFS, Babcock and Brown and its highly geared, heavily fee-laden offshoots, such as the Babcock and Brown Infrastructure Fund (all subsequently went into liquidation). Not to be left behind, Macquarie Bank (which has since revised its business model) also launched many highly geared vehicles to a hungry stream of investors who, at the time, could not get enough of these types of structures.

All this nonsense was supported by many passive and index-hugging managers lapping up every placement made by REITs, as well as by investment banks hungry for the fees attached to their new, highly geared infrastructure vehicles. As a disciplined value manager with a quality overlay, IML distanced itself from all of this nonsense – although at the time, doing so meant lagging the index and taking a fair amount of criticism that our returns were trailing those of more index-conscious managers and all passive funds.

What happened when markets corrected in 2000 and 2008?

The answer: all index funds, as well as all fund managers who decided to closely match the index in terms of portfolio construction because they were overly worried about lagging the index, were caught with stocks that, despite being large parts of the index, did not make any fundamental sense and which all virtually crashed in value. Many tech stocks fell more than 90% in 2001 while the whole REIT sector, in theory a defensive sector, dropped 76% from its 2008 peak – as shown in the graph below.

Australia’s REIT sector performance over 20 years

Source: IRESS, March 1999 to June 2019

So where are we today?

Which brings us to 2019, where, in our view we are again witnessing some fairly large price distortions and anomalies in the current sharemarket. It is a time when, not surprisingly, many are once again questioning active value managers, like IML, and questioning why IML is holding onto what seem to be many pedestrian and out-of-favour companies.

IML is underperforming and, justifiably, we are again being questioned by some as to whether the best times for active value managers are behind us. As has been the case through many of the previous booms referred to above, the current period of effervescence has been supported by ultra-low interest rates and easy monetary conditions worldwide.

These current low interest rates are forcing investors further up the risk curve into companies with perceived high growth, or a higher than average yield. This is evidenced by virtually every REIT in Australia trading well above its Net Asset Value (NAV). Many investors chase REITs because they pay an attractive yield when compared to cash or bond rates. As the share prices of these REITs rise, they become a bigger part of the index, meaning that index funds have to buy ever increasing amounts of them with every inflow.

In addition, many locally listed technology stocks of often dubious quality are trading on PE multiples in the hundreds and have collectively become a significant part of the index, as investors extrapolate current earnings growth as a certainty well into the future. This often happens when up-trending market sectors or stocks capture the imagination of momentum investors or speculators and are bid up and chased aggressively. Once these stocks’ market capitalisations make them large enough to become a part of the index, then passive/index buying tends to automatically follow despite many looking irrationally priced and overvalued. This pattern creates a vicious cycle until the music stops.

‘In many ways, the danger with the recent rise in popularity of passive and quantitative strategies is that it is legitimising certain irrational behaviour’

In many ways, the danger with the recent increase in flows into passive strategies is that it legitimises certain irrational behaviour in the market. Thus, stocks with little to no earnings, often with questionable fundamentals yet with perceived growth, are finding good buying support by the overwhelming shift to passive or quant-based strategies as their share prices rise and they become a larger part of the index.

This is occurring because by their nature, index/passive strategies do not use any qualitative factors to select securities for their portfolios.

The more money that flows into these strategies, the more the bubble in certain sectors of the sharemarket gets inflated as these stocks become a higher weighting in the index, thus attracting more buying from index/passive funds. It’s a cycle that continues unabated to direct money into the most overvalued stocks with some momentum – until some sort of reality check occurs. Then, momentum will work the other way, i.e., the more these overvalued stocks correct, the more their index weight will decline and the more selling they will attract from index/passive strategies.

Where do we see signs of irrational pricing emerging?

Several sectors seem to have plenty of blue sky priced in, with little or no regard for fundamentals. While technology stocks around the globe have performed exceptionally well in recent years, led by US success stories such as Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Alphabet, Microsoft and Cisco Systems. These companies are well established, very profitable, cashed-up tech leaders with formidable business models and a well-recognised global presence.

In sympathy with the appetite for these established tech stocks, Australia’s nascent tech sector has also been caught up in this exuberance. Many companies, such as Wisetech, Nearmap, Afterpay and Zip Co Money, have soared in value. Stocks such as these are now collectively valued at tens of billions of dollars despite their business models being largely unproven. It is fair to say that an investment in these companies is a very different proposition to investing in the US tech companies listed above.

We are also seeing several biotech or early-stage pharmaceutical companies like Avita Medical, Pro Medicus and Nanosonics soaring to billions of dollars of market value, putting these stocks on very frothy and, often, very unrealistic, valuations.

Many investors continue to pay massive multiples for a slice of the action which, as highlighted above, is further supported by the wave of passive and quant-based funds buying shares in these companies simply because they are starting to represent a larger part of the index.

At IML, we look for a number of characteristics in any stock we consider for one of our portfolios – competitive advantage, recurring earnings and quality at a reasonable price.

In our view, the valuations of many of these types of companies have lost touch with fundamentals. Yet, investors seem happy to pay earnings multiples well into the hundreds on the view that a company might be the next big thing.

While it is possible that one, or perhaps even two, of these types of companies in Australia may one day in the future end up justifying today’s sharemarket valuation of billions of dollars by earning hundreds of millions of dollars in profits in the next decade or two, the truth is that the vast majority of these types of stocks – and there are many dozen in Australia which have stretched fundamentals – will not fulfil the promise of the huge profits implied by today’s share prices and large market capitalisations.

Another good indicator that market exuberance is nearing a peak is the rising percentage of new IPOs in the US being listed with little or often negative earnings. As seen in the chart below, the last time we saw this percentage was in 2000 at the peak of the dot.com boom.

Source: Topdown Charts, Jay R Ritter

The valuations of some of the hot sectors of recent years are also beginning to be questioned, possibly indicating the bubble will soon deflate. Thus in the US, we’ve seen ride-sharing companies Uber and Lyft close recently at record lows, dropping 36% and 23%, respectively from their very recent IPO prices. In addition, many ‘unicorn’ companies which had, until recently been highly valued in the private market are now falling significantly in value as they approach IPO – office rental company WeWork, which was recently valued by SoftBank at US$47 billion, failed to get listed on the Nasdaq despite the IPO valuation being reduced to US$10 billion.

History has shown that when sharemarket corrections occur, the stocks and sectors in which the most blue sky has been priced in are always the most impacted.

Hence, in our view, it pays to be very careful of many of the stocks and sectors in the Australian sharemarket referred to above.

In the large-cap space, we are also seeing several sectors today trading at very toppy valuations as investors chase yield almost regardless of the underlying fundamentals. As previously mentioned, if one looks at REITs, for example, many are trading well above their Net Tangible Asset (NTA) base. While we acknowledge that many REITs have solid business models, with many of the attributes we look for in companies such as recurring earnings, in our opinion, many REITs are trading today at very toppy and hard-to-justify valuations.

From the charts below, we can see that the share prices of two well-known REITs are trading at significant premiums to their underlying assets.

Mirvac’s price to NTA peaked at 1.35 in recent times

Source: FactSet as of 30 Sept 2019

Dexus’ price to NTA rose to 1.35 in the last quarter

Source: FactSet as of 30 Sept 2019

While some may argue that listed REITs should demand a small premium to their NTA given the accessibility to investors, does paying a huge premium above NTA simply because the asset is listed on the exchange make a lot of sense?

This is akin to buying a property on the open market at an auction, listing it on the stock market and getting REIT buyers to pay 30-40% more for it simply because it is listed – does this really make sense?

Much of this comes down to the current ultra-low interest rate environment and the thirst for yield, almost regardless of value. Despite the significant premiums to NTAs that many of these REITs trade on, they remain popular with many investors as they offer a yield of around 4%, which is well above that available in the bond and term deposit markets.

In recent months, we have also seen a strong rally in the banking sector – a sector we have been cautious on for some time. Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA) shares recently reached a PE of 17x and above levels seen before the start of the Royal Commission. Once again, as the RBA cuts rates, many investors are flocking into shares like CBA because of the attractive dividend yield of the stock vs cash.

CBA’s PE has surpassed levels seen before the start of the Royal Commission

Source: FactSet as of 4 Oct 2019

This big rally in CBA has come despite pressure on CBA’s net interest margins and forward earnings as interest rates fall and credit volumes decline. Meanwhile, the impact of the Royal Commission will also mean extra costs for the banks in areas such as compliance, while the risk of further customer-related remediation charges in the years ahead has been elevated by the Royal Commission’s findings.

As a disciplined value manager, we have been prepared to step back from this hunt mania for what seems to be ‘yield at any cost’. In our opinion, the REIT sector looks highly susceptible to a significant pullback at some stage while we have used the rally in the Banking sector to trim our exposures. We remain very ‘underweight’ and very selective in both these sectors.

So to conclude, which strategy is better for investors?

In summary, while passive strategies will always ensure that an investor captures all the upside when markets are trending higher, their indiscriminate buying based solely on index weights also means that these strategies will end up ultimately holding many overvalued stocks and sectors when markets turn and become more rational.

On the other hand, active managers, such as IML, will go through periods of outperformance and underperformance depending on the market cycle. However, one would expect a well-resourced active manager with a proven process to be in a position to create value for investors vs the index over the longer term as they identify mispriced securities to hold over the long term or avoid in irrationally priced markets.

At IML, we remain disciplined and committed to investing in good quality companies trading on attractive valuations that we believe are well positioned over the next 3-5 years – and in companies that we believe will do well in more rational markets.

While the information contained in this article has been prepared with all reasonable care, Investors Mutual Limited (AFSL 229988) accepts no responsibility or liability for any errors, omissions or misstatements however caused. This information is not personal advice. This advice is general in nature and has been prepared without taking account of your objectives, financial situation or needs. The fact that shares in a particular company may have been mentioned should not be interpreted as a recommendation to buy, sell or hold that stock.

INVESTMENT INSIGHTS & PERFORMANCE UPDATES

Subscribe to receive IML’s regular performance updates, invitations to webinars as well as regular insights from IML’s investment team, featured in the Natixis Investment Managers Expert Collective newsletter.

IML marketing in Australia is distributed by Natixis Investment Managers, a related entity. Your subscriber details are being collected by Natixis Investment Managers Australia, on behalf of IML. Please refer to our Privacy Policy. Natixis Investment Managers Australia Pty Limited (ABN 60 088 786 289) (AFSL No. 246830) is authorised to provide financial services to wholesale clients and to provide only general financial product advice to retail clients.