By Hugh Giddy

READ

As Darryl Kerrigan famously said in the iconic Australian movie, The Castle, “It’s not a house, it’s a home, a man’s home is his castle.” Home ownership is part of the Australian dream, with many near certainties for people such as the need to get onto the property ladder early (no snakes in sight), that prices will seldom fall much and that the government and Reserve Bank will ensure that remains the case.

For Australia’s foreseeable economic future and the stockmarket, two things would seem to be key:

- Commodity prices are currently at very high levels. These underpin mining profits, mining investment, royalties and other tax revenues. While many smart people analyse and forecast prices, the most reliable observations about commodities are that they tend to be quite volatile, and that high/low prices tend to bring on more/less supply, which means extreme prices are seldom sustained. While mining is obviously key, it will not be my focus here.

- House prices and the housing sector. This drives the health of the banking sector, and household confidence and consumption. This essay explores this crucial foundation of the economy.

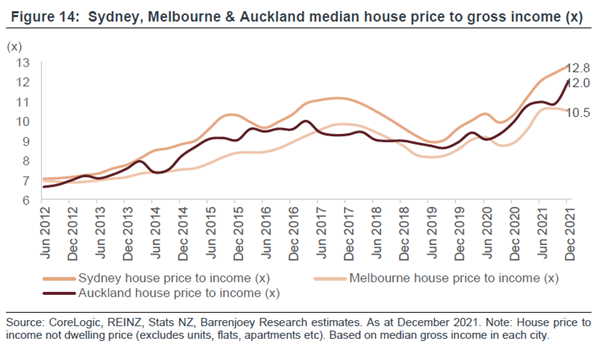

Confronted by house prices that seem to keep rising significantly in excess of incomes, a narrative of factors has evolved that justifies the upward trend, ranging from strong immigration (during Covid house prices rose strongly without this), land shortages, coastal living, rent being dead money, and others. As the chart below shows, the ratio has risen appreciably in the past decade, after rising strongly in the 40 years before the chart begins.

The more probable explanation of such rapid and continuous house price appreciation over time is the contribution of easy credit and government policy. There is an element of chicken and egg in how dependent the economy has become to a strong housing sector, as the large vested interests resulting from high prices lobby for policies such as negative gearing, home buyer grants, and instant tax write offs that underwrite conditions that bolster the broad housing industry. Rising house prices mean:

- bigger bank loans, fewer loan losses, and more home equity withdrawal, underpinning the banking sector and household consumption

- higher real estate agent commissions

- higher mortgage broker commissions and trailing commissions

- more renovations, including new bathrooms & kitchens, frequent repainting, and so forth, underpinning the building trades

- strong returns for property developers, as evidenced on the rich lists

- greater consumer confidence through wealth effects, leading to higher discretionary spending, including furniture, electronics and homewares

It is hard to estimate how many jobs rely to some degree on housing, and how many of those jobs would be at risk amid a deep and sustained pullback in house prices. Metcash, operator of the Mitre 10 franchise, estimates that of the 9 million full time workers there are 1.7 million tradies in Australia. On the transactional side, there are close to 100,000 real estate agents, and many mortgage brokers (about 8,000 businesses, presumably with multiple employees). These are just a few examples.

With so many jobs tied directly and indirectly to the housing market the authorities rush to support the housing sector whenever conditions appear challenging. Covid was no exception, with grants for major renovations and new builds, combined with record low interest rates. A boom in house prices and housing starts ensued.

Of course, continuously rising house prices has made them less and less affordable, although falling interest rates have countered this dwindling affordability. With short term rates at zero it is hard to see how affordability can improve from here without house prices falling, or rising materially slower than wages.

As the election looms and cost of living pressures rise from a variety of sources, politicians are juggling how to make housing more affordable while keeping prices high for those who own them and all the jobs that depend on prices being underpinned. Candidates focusing on poor housing affordability will no doubt repeat the mistakes of the past. Such mistakes include demand stimulus that actually pushes prices up rather than containing them, such as grants to first time home buyers, constraining interest rates, and other subsidies.

All those forecasting sustained price declines have been proved wrong and almost no one believes prices will fall in any material way, that is: a fall of over 20% that is not recouped quite quickly, resulting in widespread negative equity. However, an entrenched belief in a continually rising price trend can be a dangerous thing. It encourages high levels of leverage, limited buffers, and it removes the need for income from the asset. 28% of mortgage lending by the big four banks in Australia is now to borrowers with debt to gross income over 6x, considered “very high” leverage. Combined with negative gearing, a peculiarly Australasian tax incentive, the poor net yields from residential investment are palatable to many. Nevertheless, a continual reliance on capital gains rather than cash flow and income means that valuations are not well supported on a fundamental basis.

What does this mean for banks and the stockmarket? In a fairytale world we could keep interest rates low, making servicing a mortgage easy, supporting higher house prices and facilitating happy home-owners with growing equity and the possibility of funding renovations, yachts or holidays with equity drawdowns. This would mean continuous strong consumer demand in the economy, low bad debts, and good credit growth for banks.

However, even the Reserve Bank of Australia will have to pull its head out of the sand and see inflation has risen (latest above 5%, and interest rates, as everyone should know, are still at 0.1%). Interest rates around the world have begun to rise quite steeply to combat inflation, with New Zealand already well ahead of Australia.

As rates rise, so too will the cost of mortgages. Combined with inflation in many essential items discretionary spending is likely to come under pressure. This combined with a shift from household goods back to travel and services that people were denied during Covid, could mean a challenging outlook for retailers. Pressure on household budgets is already evident in some “trading down”. Australia faces a particularly challenging outlook with a peak of low-rate two-year fixed mortgages needing to be refinanced at probably much higher rates in 2023. CBA alone will have over $90bn of fixed rate loans maturing in 2023.

Self evidently, higher rates must be good for the banks as they can charge their customers more, or so investors believe. However, in Australia there will be price competition for deposits as banks do not have enough deposits to cover their loans. As the banks have shrunk their branch networks they have often lost touch with customers. Two thirds of all mortgage flow is now mediated through mortgage brokers who are only interested in the lending rates and turnaround times of the major banks and their competitors. Refinancing of fixed rate loans will also provide a great opportunity for brokers to churn, and any bank that is not fiercely competitive on rates will lose volume. If higher rates lead to a downturn, which seems likely albeit not certain, we are likely to see bad debts become a feature for banks after a long holiday where government income support and low rates meant that banks saw almost no bad debts.

Should this play out, we believe portfolios of reliable, defensive companies will do well among more cyclical businesses or financial businesses that have benefited from the long easy money boom.

Hugh Giddy is Senior Portfolio Manager and Head of Research for Australian equities fund manager Investors Mutual Limited.

While the information contained in this article has been prepared with all reasonable care, Investors Mutual Limited (AFSL 229988) accepts no responsibility or liability for any errors, omissions or misstatements however caused. This information is not personal advice. This advice is general in nature and has been prepared without taking account of your objectives, financial situation or needs. The fact that shares in a particular company may have been mentioned should not be interpreted as a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold that stock. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

INVESTMENT INSIGHTS & PERFORMANCE UPDATES

Subscribe to receive IML’s regular performance updates, invitations to webinars as well as regular insights from IML’s investment team, featured in the Natixis Investment Managers Expert Collective newsletter.

IML marketing in Australia is distributed by Natixis Investment Managers, a related entity. Your subscriber details are being collected by Natixis Investment Managers Australia, on behalf of IML. Please refer to our Privacy Policy. Natixis Investment Managers Australia Pty Limited (ABN 60 088 786 289) (AFSL No. 246830) is authorised to provide financial services to wholesale clients and to provide only general financial product advice to retail clients.